An old (and, alas, they’re all old now) interview with Douglas Adams from the May 1985 issue of Macworld. Transcription is via OSX’s images to text service.

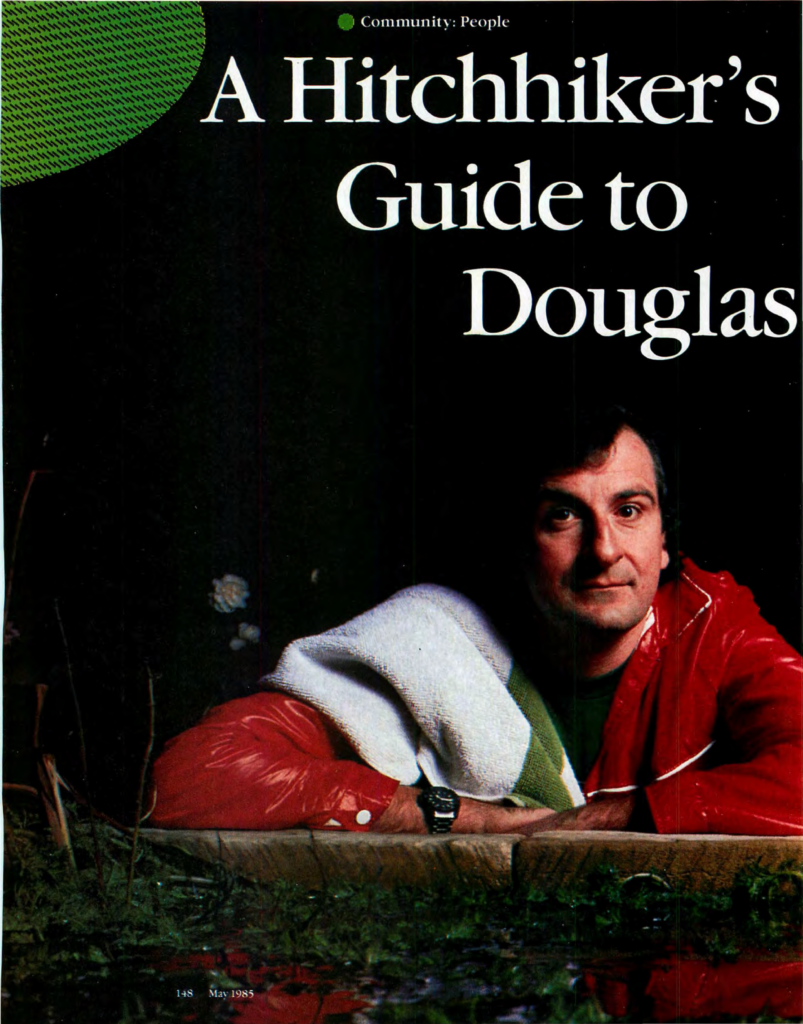

Macworld sent Contributing Editor Jeffrey S. Youny

hitchhiking to the Islington district of London in

search of Douglas Adams, author of the radio shou,

book, stage play, phonograph record, television

show. and-most recently-Macintosh interactive fic-

tion game called The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Gal-

axy. When Young found Adams, they settled into a

conversation that ranged over four days, three din-

ners. two cities astride one ocean, and innumerable

discussions on the Macintosh, music, and the mean-

ing of life in this arm of the galaxy.

Tucked away in a narrow, twisting cobblestone alley, up

three flights of stairs, and past a comfortable but by no

means opulent flat is an office as crowded and eclectic

as I expected from the tall, witty man who wrote a few

small books with characters named Slartibartfast,

Grunthos the Flatulent, and Wowbagger the Infinitely

Prolonged. The books have sold 7 million copies

worldwide, give or take a few thousand. The author is

the youngest recipient of the Pan award, which is to

British paperback publishing what a platinum album is

to the recording industry, signifying over a million

copies sold. Only Anne Frank, who was awarded the

Pan posthumously, would have been vounger.

What seemed to be a few thousand books filled

the shelves: the complete works of Dickens, Tolstoy,

Hesse, Kurt Vonnegut, John Le Carré, P. G. Wodehouse,

and G. B. Trudeau and travel guides to all corners of

the earth as well as parts of the known universe.

Games were stacked one on top of the other, including

Scrabble, Monopoly, Big Boggle, Beatlemania, and the

American and British versions of Trivial Pursuit. Sheet

music and audio cassettes occupied anv nook or

cranny that might have been empty.

A small newspaper clipping, yellow with age,

hung framed on the wall. It was the best-seller list

from the New York Times dated Sunday, December 26,

Three titles were circled in red pencil: the hard

covers Life, the Universe and Everything and The Res-

taurant al the End of the Universe and the paperback

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. All three were

written by Douglas Adams.

“As far as I know,” Adams told me, “the last British

writer to have three on the lists at the same time was

lan Fleming. What does that say about the quality of

my books?’

His office is cramped and cluttered; Adams proba-

bly never straightened up his room as a child. The

floor is covered with more books, papers, games, tele.

phones, cables, used coffee cups, an electric guitar

plugged into an amplifier that is always on, and a copi-

ous assortment of software manuals and disks.

“A writer has a built-in protection against b.s.:

there’s always the next sheet of paper.” Adams said.

“The most frustrating thing is that because of my writ-

ing style everybody thinks it’s somehow incredibly

easy, that I sit down and it all flows out perfectly. My

first, second, and third drafts are usually hopeless.

Maybe by the twentieth there’s a glimmer of hope.

“Look, sorry, are we talking about the little

white furry things with the cheese fixation and

women standing on tables screaming in early

sixties sitcoms?”

Slartibartfast coughed politely. “Earthman,”

he said, “it is sometimes hard to follow your

mode of speech.”

“The hardest part of writing for me is making it sim-

ple,” Adams said. “In a certain way having written

Hitchhiker’s originally for radio was instrumental in

developing my particular style. It was always meant to

be read out loud. Lalwars listen to the sound of my

words as I write them. On radio an idea can’t last more

than a page or two, so vou start by throwing in lots of

ideas and then cutting… and cutting..and cutting

maniacally. You cut the piece back, crumple the words,

force them together by gravitational collapse so that

whole new shades of meaning become apparent. The

language becomes richer and richer as vou compact it.

“One of the problems of being a best-selling au

thor is that publishers are locked into deadlines and

schedules,” Adams said, talking about pressures that

many writers would commit violent acts to have. “With

So Long and Thanks for All the Fish I got so far be-

hind that I had to go to a hotel in Devon and lock my-

self away to get it done.

“Maybe it’s a zen problem. Or mavhe I’ve about

run out of steam with Arthur Dent, Ford Prefect. Mar-

vin the Paranoid Android, and Zaphrod Beeblebrox.

won’t sav TIl never do another Hitchhiker book, but

certainlv not for a while

Suddenly Marvin stopped, and held up a hand.

“You know what’s happened now, of

course?”

“No, what?” said Arthur, who didn’t want to

know.

“We’ve arrived at another of those doors”

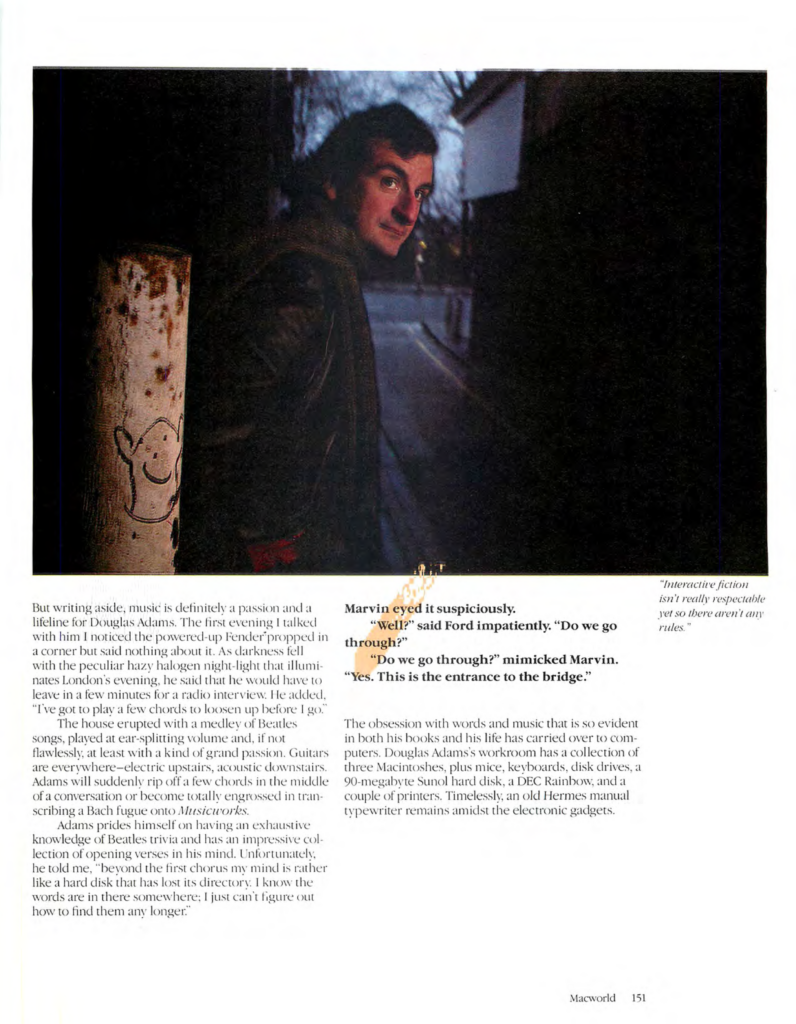

But writing aside, music is definitely a passion and a

lifeline for Douglas Adams. The first evening I talked

with him I noticed the powered-up Fender propped in

a corner but said nothing about it. As darkness fell

with the peculiar hazy halogen night-light that illumi-

nates London’s evening, he said that he would have to

leave in a few minutes for a radio interview. He added.

“I’ve got to play a few chords to loosen up before I go.

The house erupted with a medlev of Beatles

songs, played at ear-splitting volume and, if not

flawlessly, at least with a kind of grand passion. Guitars

are everywhere-electric upstairs, acoustic downstairs.

Adams will suddenlv rip off a few chords in the middle

of a conversation or become totally engrossed in tran-

scribing a Bach fugue onto Musicworks.

Adams prides himself on having an exhaustive

knowledge of Beatles trivia and has an impressive col-

lection of opening verses in his mind. Unfortunatel:

he told me.

“bevond the first chorus my mind is rather

like a hard disk that has lost its director: I know the

words are in there somewhere; I just can’t figure out

how to find them any longer.

Marvin eyed it suspiciously.

“Well?” said Ford impatiently. “Do we go

through?”

“Do we go through?” mimicked Marvin.

“Yes. This is the entrance to the bridge.”

The obsession with words and music that is so evident

in both his books and his life has carried over to com-

puters. Douglas Adams’s workroom has a collection of

three Macintoshes, plus mice, kevboards, disk drives, a

90-megabyte Sunol hard disk, a DEC Rainbow, and a

couple of printers. Timelesslv, an old Hermes manual

tvpewriter remains amidst the electronic gadgets.

“I use it when I get stuck,” he pointed out.

“There’s something wonderfully fundamental about

hitting the keys and watching them strike the page-

something a word processor will never entirely re-

place!

The computers were on constantly. Adams

hunched over in front of them, chin resting in one

hand. With the other, he pecked at the keyboard or

guided the mouse.

Adams’s fascination with computers is no idle pur-

suit. When I visited him, he was creating a complex

three-dimensional crossword puzzle, written in BASIC

that ran a bit buggily on his DEC Rainbow: He was

madlv reading up on MacFORTH for better graphics

than BASIC allowed him.

“Discovering computers last ver while I was in

Los Angeles,” Adams said, “got me interested in things

again. I was bored-a spoiled kid asking mommy what

to do next. I didn’t have any direction; I had run out of

steam. Now I’m filled with ideas again. I ve taught my-

self a little bit about programming, and I’m excited,

bubbling over with projects

Asked about the Macintosh, Adams ventured,

“Irt

clearly the product of a lot of imagination. Whereas

IBM’s end is to do business-the company identifies

how to best create and then pursue a market-at Apple

thev’re just a bunch of fanatics out to change the world

in their own peculiar way.

“I think the Mac is the kind of machine that Ford

Prefect would own. When I started the whole Hitch-

hiker’s saga, I was reacting to the serious science fic-

tion typified by the British television show Dr: Who.

My original concept behind Ford Prefect was that if

presented with the choice of saving the planet or going

to a good party, Ford would choose the part: Wouldn’t

a fellow like that have a Mac?”

“Slowly, with great loathing, he stepped toward

the door, like a hunter stalking his prey. Sud-

denly it slid open.

“Thank you,” it said, “for making a simple

door very happy.”

In his novel The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy,

Douglas Adams tells of a supercomputer called Deep

Thought, which, when asked the meaning of “life, the

universe, and everything,” answers “Forty-tWo.

While the Mac must be nearlv the opposite of

Deep Thought, it nonetheless has inspired Douglas

Adams in a wav even he never anticipated. When it was

first suggested that he turn Hitchhiker’s into an inter-

active fiction game (see “> Wake Up to Adventure” in

this issue), Adams was less than enthused. “All I could

think of were those games where you’re forever shoot-

ing down rockets,” he said. “So I thought, no thanks.

But then he plaved a few of Infocom’s interactive

fiction games and reconsidered. After all, Adams is an

author whose cross-media skills are about as sharp as

they get. The idea of transferring what was originally a

radio show and then a novel onto a magnetic disk-

after everything else Hitchhiker’s has been translated

into-was too challenging to ignore. So in earlv 1984 he

teamed up with Steve Meretzky, who was responsible

for the Infocom games Planetfall and Sorcerer, to

create The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy-the com-

puter game.

“I enjoved writing the game because the interac-

tive fiction medium is such a young field, Adams told

me, “that everything vou do is new. It must be rather

like what working in the movie business was at the

turn of the centurv. Interactive fiction isn’t reallvre-

spectable vet so there aren’t an rules about what can

and can’t be done.

“For instance. I believe this is the first program

that deliberatelv lies to vou, tells vou one thing and

eventually admits, if vou keep asking, that it has misled

vou.

As Adams wrote text in his London office. Meret-

zky wrote the program in Boston. They communicated

via electronic mail on a commercial electronic bulletin

board service.

*We started by developing a kind of horizontal

and vertical branching network.” Adams explained. “It

would have been pointless to do a linear trot through

the book. The idea we came up with was to make the

process something like figuring out how to go through

the neck of a bottle. Once vou start to think in the

strange logic we set up, vou can begin to negotiate

your way around the game pretty easilv: But until vou

do, vou’ll have a tough time. There’s no necessarilv

correct answer at any point, and all vour previous

choices influence what vou can do. So not only is there

no absolutelv correct route, there is no way that vou

will follow the same path twice” The coauthors even-

tally sweated out a conclusion while pounding up

and down a beach in Devon. Adams said.

The program was written in a subset of LISP and

makes extensive use of a parser written at Infocom. Ac-

cording to Adams, the parser “sort of understands

complicated sentences. The parser takes a plaver’s in-

put and translates it into a form that the program can

answer.” That may be true. but I found a number of

Hitchhiker’s answers incomprehensible, which is

probably just as Ford Prefect and Douglas Adams

intended. Judging from the messages on the Game sec-

tion of The Source, I wasnt alone.

“Such subtlety …

” said Slartibartfast, “one has

to admire it.”

“What?” said Arthur.

“How better to disguise their real natures,

and how better to guide your thinking. Sud-

denly running down a maze the wrong way, eat-

ing the wrong bit of cheese, unexpectedly drop-

ping dead of myxomatosis. If it’s finely

calculated the cumulative effect is enormous.

He paused for effect.

One afternoon during my visit Adams tapped into The

Source in Virginia, where it was morning, and we took

a look at the messages about his game. asked if he

ever identified himself and answered some poor

bloke’s plea for help.

“I’ve tried it a few times.” he said with a smile.

“but nobodv believes that it’s me.

That dav The Source carried confused messages

aplenty from Hitchhiker’s pavers in various stages of

exasperation. As we scrolled through the messages,

Adams laughed gleefully: Echoing a baffled bulletin

boarder. I asked him what the point of the game is.

“That’s for vou to find out,

” he said. “The object of

the game is to find out what the object of the game is.

But I will tell vou that vour score is an index not just of

how far you’ve gone along the adventure, but also of

how happy you should be at that point.

“For instance, it vou enjor the beer when vou

drink it, vou’ll get more points. Believe me-if you get

far enough inside the game, you’ll need all the points

you can get!”

So is he happy with the game? “As happy as I ever

am with anything I do. I mean, I can always see ways

to make something better once its finished. In this

case I think the whole experience only shows me the

possibilities.

“I think software development right now is some.

thing like the recording industry would be if recording

engineers were the only ones making records. Any art

ist can make music without knowing how to wire mix-

ing boards or understanding how recording heads

work because the technology has been simplified and

made accessible. I think the Mac demonstrates how

simple operating and programming a computer will

eventually become. When that happens, writers and

artists will create their own programs, and you’ll see

software available like records and tapes are todil

By that time Douglas Adams will have a few more

clippings framed on his wall, showing one or two of

his programs in software’s Top 40.

Jeffrer S. Young is d

Contributing Editor of Macworld